By Zachary Ochieng

NAIROBI - Michael Onyango, 26, a resident of one of Nairobi’s poorer neighborhoods, groans on his bed at the Kenyatta National Hospital, East Africa’s largest teaching and referral institution. In another ward, his wife, Jane, and two-year-old daughter, Magdalene, wait patiently for the nurses to do their rounds.

The Onyangos have been admitted here following a diagnosis of typhoid and amoebic dysentery after drinking sewerage water. They had also bathed in the foul water.

“We had gone for two days without a shower due to the current water shortage and I had no money to buy even a gallon,” Mr. Onyango, a construction worker recalled from his hospital bed. “When I saw a burst pipe splashing water near my house, I called my wife to join me in fetching the water. This was an opportunity we could not lose.”

Even though the water did not appear clean, Mr. Onyango did not give it a second thought. “All my family needed was water. To us, the source did not matter.”

Two days later, a crew from the Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company arrived to seal the broken pipe. By then the Onyangos had begun suffering bouts of diarrhea and vomiting. They had rashes all over their bodies. When the crew told them that the broken pipe had been gushing sewage, the family went to a neighborhood dispensary. The dispensary sent immediately to Kenyatta National Hospital.

The family joined a growing number of people suffering from water-related illnesses in Kenya and around the world. Almost half the population of the developing world is suffering from one or more of the main diseases associated with inadequate provision of water and sanitation, according to WaterAid, an international charity. Its mission is to overcome poverty by helping the world’s poorest people gain access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene.

Half of the developing world’s hospital beds are occupied by patients suffering from water-related diseases. Worse still, 884 million people, roughly one eighth of the world’s population, do not have access to safe water. Some experts say the total is even higher. Each year, 1.8 million children die as a result of diseases caused by unclean water and poor sanitation. This amounts to around 5,000 deaths a day.

The debilitating illness that befell the Onyangos is a story replicated in slums and middle class areas of Nairobi as a water shortage continues to bite. Records at Kenyatta National Hospital indicate that water borne diseases such as diarrhea and gastroenteritis are the second leading causes of mortality in Kenya after HIV/AIDS.

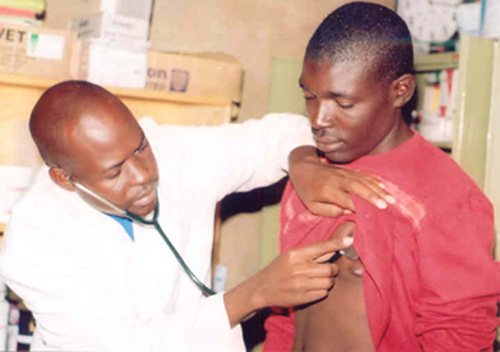

In the sprawling Kibera area of Nairobi, sub-Saharan Africa’s largest slum settlement, hardly a week passes without such a case being recorded. “Due to the persistent water shortage, we advise the patients to boil their drinking water since they do not know the source of the water that vendors sell to them”, says Dr Frederick Ochieng who runs a clinic in Kibera.

Nairobi’s reservoirs have been running particularly low on water. Experts say the lower water levels are the result of the destruction of forest lands that have historically absorbed water that eventually reached the reservoirs. Land developers are being blamed. Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company executives say they expect rationing of water to be necessary until the reservoirs are replenished by seasonal rains. #