By Christopher Pala

HONOLULU—Forty years ago, Honolulu was cooled by steady trade winds blowing across the beaches from the northeast. People in downtown shops and offices opened their windows to let in the breeze. But today the skyscrapers that rise in the capital of Hawaii are sealed. They depend on air conditioners that devour electricity and heat the atmosphere with their exhaust.

That’s about to change.

Hawaii relies on oil for more than 90 percent of its energy needs, a higher proportion than any other state. Honolulu, the state’s biggest consumer of electricity, is about to become the first warm-weather city in the world to have its downtown cooled by sea water pumped from the deep. The new system is designed to use less electricity and reduce greenhouse emissions.

Until mass tourism in the 1970s caused high-rises to sprout from Waikiki to Pearl Harbor, downtown Honolulu was a city of widely spread-out buildings shaded by giant trees rustling in the cool trade winds that sweep from the Pacific Ocean across this isolated archipelago 1,400 miles north of the equator.

But many of the trees have yielded to high-rises that have turned the city center into an island of heat and become a strain on the state’s over-extended power-generation system.

Honolulu won’t be the first place where offshore water has been used for air conditioning. Toronto and Stockholm are among the few places that have tapped cold water – from Lake Ontario and the Baltic Sea – to balance temperatures inside large city buildings, notably to counteract the heat generated by hot computer servers and telephone exchanges. Cornell University in upstate New York uses the same technique. It gets its water for cooling from Cayuga Lake.

But neither Toronto nor Stockholm nor Cornell have gone as far with this process as Honolulu intends to, said William M. Mahlum, the president of Honolulu Seawater Air Conditioning, the company that is building the $240-million system in Hawaii.

“This is the first time,” Mr.Mahlum said, that offshore water “will be used to cool a whole warm-weather city center year round. Mr. Mahlum said he expected construction to begin in mid-2011 and to be finished in 18 months.

At that point, 45 buildings in downtown Honolulu will be using the system. Mr. Mahlum said the neighboring Waikiki district would probably be next. “All you need is a relatively steep coastal slope and concentrated demand,” he said. “We’ve commissioned satellite studies and found at least 50 good sites just in the continental United States.”

The system will save clients about 20 percent in cooling costs, Mr. Mahlum said. It will reduce power use by 75 percent or about 77 million kilowatt-hours a year, he said, and cut emissions of carbon dioxide, the main gas that causes global warming, by 84,000 tons a year.

Ingvar Larsson, Honolulu Seawater’s Vice President of Engineering, said the sea water cooling system will reduce the use of toxic refrigerants and will save 260 million gallons of drinking water annually that were otherwise used by air conditioners.

Environmentalists like the project. Waving at the Pacific Ocean just outside his office window, Jeff Mikulina, executive director of the Blue Planet Foundation, which promotes clean energy, said: “We have a built-in refrigerator right in our back yard. It makes good sense to tap into it and let nature do some of the work for us.”

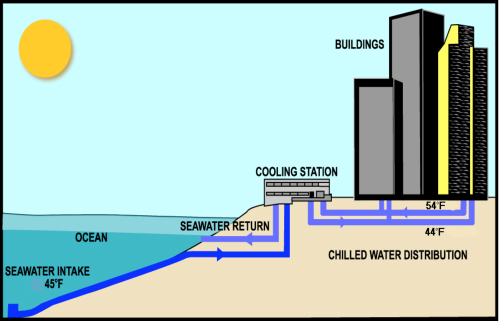

The system starts with a pipe that goes four miles out to sea, drops to a depth of 1,700 feet and brings back to shore water at 45 degrees Fahrenheit. The saltwater goes through a heat exchanger that cools freshwater circulating in a closed loop that will run from the exchanger to the 45 buildings.

The freshwater loop is necessary because salt-water is corrosive and would eventually damage the equipment. The cool freshwater replaces the energy-hungry chillers and compressors used in traditional air conditioning. As for the warmed sea water, it will be returned to the ocean at 56 degrees at a depth of 200 feet where the natural temperature is also 56 degrees. That feature was built into the process to avoid changing the ocean environment.

Overall, the system will not warm the ocean, according to Mr. Larsson, the vice-president for engineering. “If you look at the heat we emit in both the ocean and the atmosphere,” he said, “it’s 40 percent less than a conventional air conditioning system. And, of course, by cutting greenhouse gases, we slow global warming.”

Peter Rosegg, a spokesman for the Hawaii Electric Company, praised the project. He said the system would reduce electricity generation in Hawaii by one percent – or the equivalent of one year’s worth of growth in demand across the state.

“By reducing our load, it allows us to increase our reliability to other customers,” he said. “One percent may not seem like much, but this is an important one percent because the downtown area has banks and medical centers that require very reliable power.”

Sea water cooling, Mr. Rosegg said, is much more consistent than wind and solar-generated electricity, which vary with weather conditions.

Still, scientists have concerns. David Karl, a University of Hawaii microbiologist, said the system has one potential flaw. At 1,700 feet, where the chill water is collected, there are more chemical nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen than at the surface. The sea water that is returned to the ocean at 200 feet will bring along the nutrients from the lower depths. And that worries Dr. Karl. He says the nutrients could cause algal blooms with a wide variety of possible effects, ranging from providing nutritious food to fish and other marine life to poisoning the fish, depending on the algae. Dr. Karl said he has set up a team of scientists to monitor the environmental impact of the system.

Hawaii is the birthplace of sea water air conditioning technology. The Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii Authority built the first ocean thermal energy conversion system on the Big Island in 1974.

The objective was to see if water temperature differences between the deep and the surface could be economically turned into electricity. The answer was: not yet. But as a side benefit, the laboratory created the world’s first air conditioning system using cold sea water. Nearly 40 years later, it is still cooling offices at the research center. #